Check out my publications on this topic:

Roseroot: a rare plant

Leedy’s roseroot (Rhodiola integrifolia subsp. leedyi, Crassulaceae) is a cliff-dwelling succulent listed as threatened under the US Endangered Species Act. For my Master’s, I learned about the ecology and conservation of this amazing subspecies!

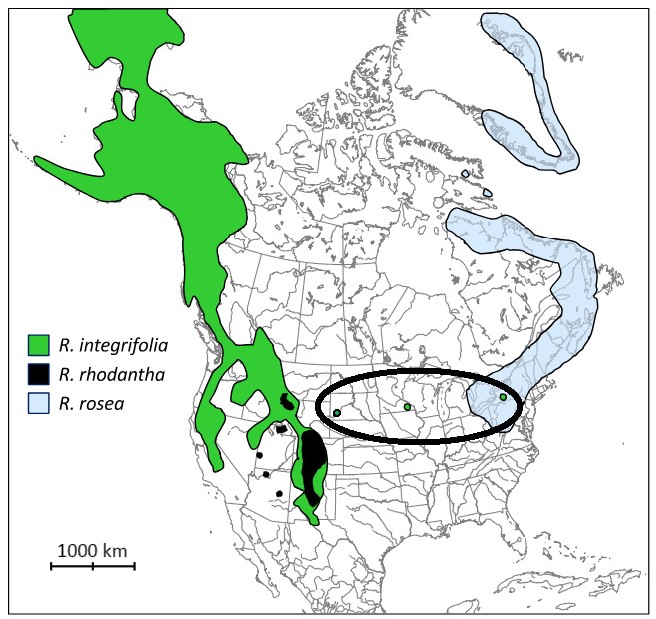

The map below shows that the genus Rhodiola in North America is restricted to northern and alpine regions. Leedy’s roseroot is a subspecies of the more widespread R. integrifolia that exists only as disjuncts in New York, Minnesota, and South Dakota–indicated in the black circle on the map. In these non-alpine zones, Leedy’s roseroot persists in relictual populations on moist cliffs. I am one of the only people in the world to have visited every population of Leedy’s roseroot!

- Distribution map. Adapted from: Guest HJ, Allen GA. 2014. Geographical origins of North American Rhodiola (Crassulaceae) and phylogeography of the western roseroot, Rhodiola integrifolia. Journal of Biogeography 41:1070-1080.

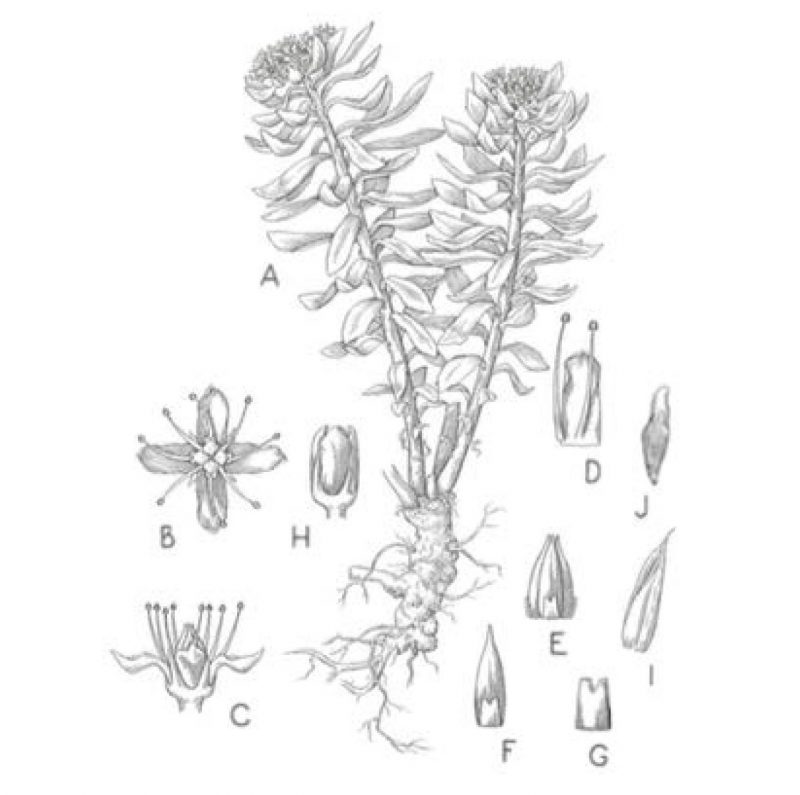

- Floral morphology. Adapted from: Clausen RT. 1975. Sedum of North America north of the New Mexican plateau. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Leedy’s roseroot has flowers typical of the succulent family, Crassulaceae, except for that it is dioecious–it has male and female flowers on separate plants. The flowers smell nice and can range from yellow to peach to dark red. The plants are long-lived perennials with crazy thick rhizomes that may act as storage organs in the harsh environments they inhabit.

- The Leedy’s roseroot type specimen. I took these photos at the University of Minnesota herbarium (https://www.bellmuseum.umn.edu/plants/)

- In this herbarium vocher you can see life stages, from seedling to adult.

- I like this herbarium specimen because you can see the persistend (“marcesent”) flowering stems, hypothesized to be retained for protection if the rhizome and the seeds within the dry follicles.

- Seedlings

- Yellow male flowering

- Red male flowering. Photo by John Wiley.

- Female flowers. Notice that most flowers have 4 carpels, but some have 5+! Photo by John Wiley.

- Females with lobed leaves. Photo by John Wiley.

- Rhizome sticking out of the cliff

Minnesota

Notice the blocky limestone. Also notice the binoculars: a crucial cliff-sampling methodology. Photo by John Wiley.

Each disjunct has its own unique qualities. Minnesota is where the subspecies was first documented by John Leedy in the 1940s. This disjunct lies within the Driftless Area, an unglaciated portion of the upper Midwest known to contain other glacial relict species–when the glaciers wiped out the rest of North America, relict populations hung on in the Driftless Area. These cliffs are calcareous, made of blocky dolomitic limestone.

- Limestone cliffs tower above a tributary of the Root River

- Ladders: another crucial cliff-sampling technique. Photo by John Wiley.

- Ladders, lichens, and Leedy’s. Photo by John Wiley.

- The cliffs in Minnesota are maderate, meaning they have ice caves at their base that exude cold air well into the summer. Glacial relicts, indeed.

- Leedy’s and bulblet fern (Cystopteris bulbifera), an interesting species that propagates itself via asexual bulbils. Photo by John Wiley.

- The Minnesota flowers are much redder than their New York conspecifics. Photo by John Wiley.

South Dakota

Rapelling, a final crucial way to sample cliffs.

The South Dakota disjunct was recently identified using genetic methods. This population is in the Black Hills region–also an area known for its unique flora. Although the Black Hills are geographically close to the Rockies where the most common subspecies of Rhodiola integrifolia occurs, the Black Hills have a completely unique geologic history compared to the Rockies. This area is dominated by acidic, granite cliffs.

- The Black Hills are especially famous for this cliff! This picture is blurry because it is taken from very far away–I refused to pay to park at the Very Crowded National Monument Parking Lot (TM)

- The highest peak in the Black Hills is Black Elk Peak. Here is the view from the watch tower at the top!

- South Dakota Leedy’s roseroot, growing out of mosses (Atrichum and Brachythecium?)

New York

Enjoying Finger Lakes wine at Glenora Wine Cellars. Photo by Don Leopold.

I did the majority of my research on the largest population of Leedy’s roseroot, in the Finger Lakes region of New York. This area is not necessarily well-known for its flora, but it is world-renowned for its wine production! The cliffs along the southern portion of Seneca Lake where Leedy’s roseroot grows are composed of horizontally-plated calcareous shale.

- Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) invades the talus below the cliff in New York. This is a big challenge to Leedy’s roseroot conservation in New York.

- Marcesent flowering stems hanging down

- A local land owners’ goats using their cliff climbing skills to help with fieldwork

- Another New York state rare species, Draba arabisans (Brassicaceae)

- Bluebell, Campanula rotundifolia

- Columbine, Aquilegia canadensis

- Hairy beardtongue, Penstemon hirsutus

- Growing Leedy’s roseroot to plant on the at SUNY-ESF, Syracuse, NY

- Happy flowering female at the green roof!

Comments

Roseroot — No Comments